In 2007, Elaine Brouwer unpacked some important ideas on assessment in the pages of the Christian Educators Journal. It was a remarkable article. One concept from that article has remained front-of-mind for me over the years: Assessment is best done with students, and when it is, it can be a blessing. The idea of assessment with students means giving over some of the traditional responsibility of assessment to students themselves, a process often referred to as peer and self-assessment. Assessment, simply put, is the process of gathering information about learning. Peer and self-assessment requires teachers to believe that students are capable of receiving and acting on this information.

There are many strategies available for peer and self-assessment. Teachers need to make decisions in the specific context of their classroom, guided by policies established by their individual boards and administrators. Not all techniques and strategies fit equally well in every context. We need a framework that can be used by teachers in their decisions about assessment within their particular context, whether that is assessment of/for/as learning or teacher/peer/self–assessment. In this article, I explore an assessment framework that I have found helpful in my own practice. It is rooted in a restorative practice paradigm, one that combines transparent expectations for learning with appropriate and flexible supports. Following this, I discuss some ways in which I have sought to implement this framework to increase the effectiveness of peer and self-assessment with my students.

Restorative Assessment

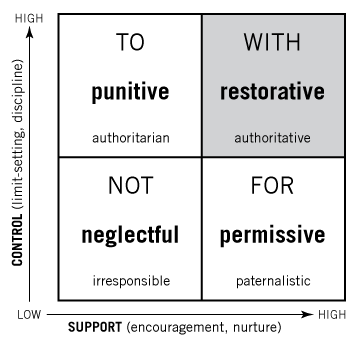

I have frequently used the term restorative assessment in my B. Ed. classes. This term is rooted in a very basic understanding of restorative practice. According to Amstutz and Mullet, restorative practice is a “long-term process that hopefully leads our children to become responsible for their own behavior” (10). Ultimately the focus is on teaching students a process by which they see their actions in the context of community and then respond appropriately when conflict occurs. Wachtel offers a helpful matrix to understand restorative practice. By aligning levels of behavioral control—found in the form of limit-setting or behavioral expectations—with support, Wachtel illustrates different forms of discipline. Low expectations accompanied by low support create a neglectful environment. These same low expectations when met with high levels of support create a permissive environment. When high expectations are met with very little support, a punitive environment is created. Finally, Wachtel arrives at a restorative environment, where high expectations are met with high levels of support.

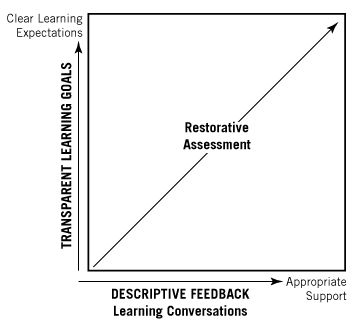

Using Amstutz and Mullet as a starting point, I propose the following: Restorative assessment is a long-term process that leads students to become increasingly responsible for their own learning. With this definition in mind, I return to Wachtel’s grid. It is not my purpose here to discuss what neglectful, punitive, and permissive assessment might look like (although there may be a need for such a discussion). Rather, I would like to turn our attention to the top-right corner of Wachtel’s grid, where teachers take an authoritative stance while assessing with their students. In this quadrant, I reimagine the vertical axis as clear learning expectations. The horizontal axis is defined as appropriate support.

When I consider peer and self-assessment within this framework, the following idea emerges: Peer and self-assessment can be effective when students are very clear about their learning goals and have been taught ways in which they can understand and respond to their progress towards those goals.

Transparent Learning Goals

Peer and self-assessment require that learning goals be transparent, clearly stated, and easily understood. This is most effective when teachers and students set the learning goals together. The teacher is ultimately the one who connects the goals to the essential learning/curricular outcomes. Students, however, can take part in determining the nature of the journey that is taken to achieve these outcomes. They can also take part in setting criteria by which their journey will be assessed. The activity of determining expectations and criteria together provides crucial assessment information. As Davies writes:

When we ask students what is important in creating a map, writing a story, doing a research report, or presenting to a small group, they get a chance to share their ideas. When teachers involve students in setting criteria, they learn more about what the students know, and students come to understand what is important while they learn. (55, 56).

When we involve students more often in setting their own learning goals and judging what criteria should be used to assess their progress, students become more engaged from the start and may gain understanding even through the process of deciding what and how to learn.

Consider the following example: If I were teaching a class how to write a persuasive essay and wanted to involve students in setting learning goals and establishing criteria, I could do the following:

- have the students read a number of persuasive essays;

- ask them to discuss and write down the different characteristics of these essays;

- have them decide which essays are most effective and why;

- have them decide which ones are least effective and why;

- identify the common characteristics of an effective persuasive essay based on what they have seen;

- work together to create success criteria, or a list of things to look for (e.g., “This is what we look for when we write a persuasive essay . . .”).

Rather than simply telling students what a persuasive essay looks like, the process described above triggers prior knowledge about essay writing, engages students in discovering for themselves what makes a good essay, and leads towards a common understanding of what is required to write effectively. This approach provides a path for students to become increasingly responsible for their own learning. Not only do they learn how to write the essay; they learn how to learn how to write the essay.

Appropriate Support: Descriptive Feedback and Learning Conversations

To move in the direction of students becoming increasingly responsible for their own learning, students need a framework for support. This framework should enable teachers to show students how they are doing in their progress towards the goals and to encourage students to assess this progress for each other and themselves. Descriptive feedback and learning conversations are important for such assessment.

Descriptive feedback is an essential element within this assessment framework. It is, however, an element of learning that needs to be clearly understood and carefully applied. According to Wiggins, descriptive feedback must be characterized by the following: It must be goal-oriented, tangible and transparent, actionable, user-friendly, timely, ongoing, and consistent. Simply stated, descriptive feedback must be phrased in such a way that students can quickly understand how it will help them achieve their goal. Chappuis and Chappuis use the following three questions to achieve this purpose:

- Where am I going?

- Where am I now?

- How can I close the gap?

Teachers can model effective feedback by using this three-question approach. Once the teacher presents this format, students can use it to provide feedback to each other through peer assessment, and eventually use it to assess themselves. Such feedback is effective only when students know where they are going in the first place. Consider the persuasive essay example once more. Students have taken part in determining what to look for in a good essay in a previous lesson. They can now refer to these criteria as they give feedback to each other during the writing and editing phase.

Learning conversations are also an important element of assessment. Such conversations often take place near the end of the learning cycle, once there is a product or a performance to talk about. Learning conversations offer an opportunity for reflection and can be used as a form of summative assessment. According to Davies, learning conversations can be face-to-face or written, as in a journal.

Like descriptive feedback, learning conversations can be modeled using templates or forms, with prescribed questions such as the following: Which assignment are you most proud of? Why? Which assignment gave you the most difficulty? What did you learn from it? Conversations can also be structured to follow a pattern similar to the questions used in restorative practice:

- What happened? (How does this assignment show what you have learned?)

- What were you thinking about when this happened? (Why did you do decide to do this the way you did?)

- What have you thought about since? (Now that you are done and have seen other examples of this work, what do you think?)

- What will you do to be more effective the next time? (How will you improve?)

Much like the three-question descriptive feedback format, a learning conversation script can be taught and modeled by the teacher so that students can engage in their own conversations with each other. The process provides crucial assessment information, but also teaches students how to reflect on their own learning in the future.

Conclusion

If the goal of assessment is to enable students to become increasingly responsible for their own learning, peer and self-assessment are essential components of the school experience. Does this mean we educators are trying to teach ourselves out of a job? No, but it might mean we need to rethink what we do in the classroom. Within the restorative assessment framework described in this article, the achievement of learning goals could begin with teacher assessment, then move towards peer assessment, and finally to student self-assessment. When students can assess themselves, we know they have learned. Once we know this, the goals change, the bar is raised, and the journey begins anew.

Works Cited

- Amstutz, Lorraine Stutzman and Judy H. Mullet. The Little Book of Restorative Discipline for Schools: Teaching Responsibility; Creating Caring Climates. Intercourse, PA: Good Books, 2005.

- Brouwer, Elaine. “Assessment for Learning: A Blessing for Our Students.” Christian Educators Journal 47, 2 (2007): 6–9.

- Chappuis, Stephan, and Jan Chappuis. “The Best Value in Formative Assessment.” Educational Leadership. 65.4 (2007/2008): 14–18.

- Davies, Anne. Making Classroom Assessment Work, 3rd Edition. Courtenay, BC: Connections Publishing, 2011.

- Wachtel, T. “What Is Restorative Practice?” International Institute for Restorative Practice. <http://www.iirp.edu/what-is-restorative-practices.php>. Accessed October 26, 2013.

- Wiggins, Grant. “7 Keys to Effective Feedback.” Educational Leadership. 70.1 (2012): 11–16.