This century hosts one of the first generations—according to the late Arnold Toynbee—that does not deliberately teach morality and ethics to children in school. Caldecott’s book provides a past, present, and future view of the importance of educational foundations. In the process of examining what is relevant in an age when educational and relational flourishing are both welcome and essential, Caldecott opens the door for educators to consider thoughtfully the power and beauty of words as philosophical positions from which to seek truth.

Caldecott, a Catholic educator, divides his book into seven distinct sections. In his first section, he looks at the need for foundations as an act of mission and freedom for the growth of the heart. He then examines the child as person and the teacher as nurturer from the Catholic philosophical roots of the Trivium. This provides a segue into the next three sections of language termed remembering (grammar, mythos and imagining); dialectic (thinking, logos, and knowing the real) and speaking (rhetoric, ethos, community in the real). He enfolds all three into his last two chapters on wisdom and love.

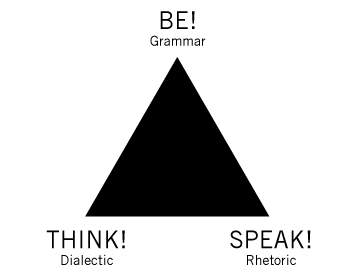

Caldecott’s message centres on the belief that the greatest threat to our civilization is philosophical. Educators today no longer hold fast to classical education as a search for truth, beauty, and wisdom. This wisdom is what he draws on to explore a Catholic philosophy of education. He features this in a simple triangle (15):

From this diagrammatic trinity, Caldecott suggests a curriculum built around storytelling, music, exploration, painting, drawing, dance, drama, and sport. Through religious education—the form and basic skills of word use—all of these components are intertwined within the goal of achieving a philosophical and moral education.

Rather than reiterate the content of Caldecott’s work (it is best to read it to discover that), I will focus on key aspects of interest to a Christian educator. After examining the work of John Dewey, expounding on the significance of play in fostering imagination, and linking play realistically to life, Caldecott postulates that if we cannot learn to attend and focus through play, it may be impossible to attend and focus in prayer. In this light, the key charge of the teacher is to teach children how to listen and focus so that attention to and in prayer can be lovingly nurtured.

In Caldecott’s view, a philosophy of education starts with the premise that the human person should be educated for relationship, attention, empathy, and imagination.