This article was first presented as an address for the 100th Anniversary Celebration of Northern Michigan Christian School, in McBain, Michigan in May 2011.

It is an honor to be able to join you as you celebrate one hundred years of Christian schooling here at Northern Michigan Christian School. I never cease to be amazed by the communities that sustain Christian schools, against so many odds and off the radar of our cultural mainstream. According to so many metrics, you shouldn’t still be here! Economic pressures, community fatigue, and the trajectory of secularization all make the reality of Christian schools a veritable institutional miracle.

But whether it’s McBain, Michigan or Waupun, Wisconsin, or Smithville, Ontario, these Christian school communities are a testimony to a God who is faithful to his peculiar people. And they are testimony to a Spirit-led people who are committed to goods beyond the bottom line—who so value the formation of their children that they are willing to set aside other pleasures of “the good life” in order to provide a faith-full education for their young people. The centenary of Northern Michigan Christian School is a witness that you are a community invested in “[telling] the next generation the praiseworthy deeds of the Lord” (Ps. 78:4).

This would be an easy time to get nostalgic—to recall wistfully the old days, some golden age gone by, to pine for “the way things were”—which usually comes with a kind of resignation that those days are gone, that we’re just waiting for the inevitable dwindling and denouement. But Christians have a very different sense of time: in the words of that immortal Michael J. Fox movie, God calls us “back to the future.” When God constantly enjoins his people to remember, he is always asking them to remember forward, to remember for the sake of the future. Yahweh presses Israel to remember the covenant and their liberation from Egypt, not so they can wallow in wistful memories of bobby socks and letterman jackets and kvetch about the “good ol’ days.” They are called to remember because God is calling them to something—to the Promised Land.

We need to appreciate how countercultural this sense of time is. We live in an age that is easily attracted to nostalgia. Whether it’s our fascination with Mad Men or our fixation on the Founding Fathers, we are easily duped into hiding in an idealized past. Indeed, just recently I read of a strange new phenomenon: the adult prom (Medina). This would be funny if it wasn’t about the saddest thing I’ve ever heard of: adults with children and mortgages and minivans trying to relive their adolescence, largely because they inhabit a culture that has encouraged them to never grow up.

When Christians remember, we are not retreating to the past; we are being catapulted toward a future. God’s people inhabit time in this strange tension, where we are called to remember so that we can hope. When Jesus enjoins us to eat and drink in remembrance of that Last Supper, he also points us toward the future: we celebrate the Lord’s Supper “until he comes,” and so the remembrance is really just a foretaste of that coming feast. Our traditions are the gifts that propel us toward the future with hopeful expectation. Christians inhabit time as a stretched people.

So let’s not confuse a celebration of faithfulness with a mere trip down memory lane. Let’s use this as an occasion to think about the future of Christian education, to hope with God-sized expectations about what the Spirit is going to continue to do here at Northern Michigan Christian School. Because Christian education isn’t just something that’s nice while it lasts; it might just be crucial for future of the people of God. Indeed, I think Christian schooling is an incredible opportunity in our postmodern context, and it might be more important now than ever.

I would like to make this case by considering the centrality of story to Christian education. Christian education tells the story of God’s redemption; indeed, Christian education is another way of inviting young people into that story. But we also need to appreciate that we learn by stories.

Learning by Stories

Let me begin with what might sound like a disconcerting thesis: Christian education is not fundamentally about knowledge. Christian schooling is not primarily about the dissemination of information. Education is not only or fundamentally about filling our intellects. And this is because we are not primarily inanimate thinking objects. Students are not brains-on-a-stick with idea-receptacles just waiting to be filled with information.

No, we are not thinking objects; we are lovers. God has made us by and for love. As Saint Augustine prayed in his opening to the Confessions, “You have made us for yourself, and our hearts are restless until they rest in you.” In this biblical picture of the human person, the core of our being is the heart, the seat of our passions, desires, and longings—the fulcrum of our love. And it is from out of the heart that our action flows. While we tend to assume that we think our way through the world, in fact it is our love that governs and drives our action. The center of gravity of the human person isn’t located in the head; it’s located in the gut. So the most formative education is a pedagogy of desire.

While we are what we love, what we love is precisely what’s at stake. Our love can be aimed at very different ends. We can desire very different “kingdoms.” While we are made to love God and his kingdom, we are prone to wander, looking for love in all the wrong places. So our love needs to be trained; our desire needs to be “schooled.” This is why, in his letter to the Philippians, the Apostle Paul first prays for their love: And this I pray: that your love may abound still more and more in real knowledge and all discernment, so that you might determine what really matters (Phil. 1:9–10, my translation). Love precedes knowledge. Not only do I believe in order to understand, I love in order to understand.

So our most basic and fundamental and formative education is a sentimental education—an education of our sentiments, our love and desire. New York Times columnist David Brooks has described this as our “second” education (Brooks 336–360). He puts it this way:

Like many of you, I went to elementary school, high school and college. I took such and such classes, earned such and such grades, and amassed such and such degrees.

But on the night of February 2, 1975, I turned on WMMR in Philadelphia and became mesmerized by a concert the radio station was broadcasting. The concert was by a group I’d never heard of—Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band. Thus began a part of my second education.

We don’t usually think of this second education. For reasons having to do with the peculiarities of our civilization, we pay a great deal of attention to our scholastic educations, which are formal and supervised, and we devote much less public thought to our emotional educations, which are unsupervised and haphazard. This is odd, since our emotional educations are much more important to our long-term happiness and the quality of our lives (Brooks, “Other Education”).

There are two things to take away from Brooks’s account: first, what he’s calling our “second” education—our “sentimental” education—is actually the most fundamental, the most basic. It makes the biggest difference. Second, if Brooks was schooled by Bruce Springsteen, then this sort of affective education happens everywhere. This sort of sentimental education is not confined to classrooms and lecture halls. This education spills over our institutional barriers; our sentiments are being educated all the time. Our culture is rife with pedagogies of desire.

Now what does this have to do with Christian education? Well, at least two things: First, we need to realize that the competitor for Christian education is not the public schools—it is all of the pedagogies of desire that are operative across our culture, in all of the secular liturgies we’re immersed in that covertly form our loves. If a Christian education is going to contribute to the formation of kingdom citizens, then it needs to be a counter-formation, countering the pedagogies of desire that would aim our love at rival versions of the kingdom. We—and our children—are immersed in affective sentimental educations all over the place: at the concert, in the cinema, at the stadium, at Wal-Mart, or on the national mall. These are loaded spaces that come charged with their own vision of the good life, their own implicit vision of the kingdom. These are not just places to go and things to do; they do something to us: they “educate” our hearts, often apprenticing us to a disordered, rival vision of the good life. And over time, that education works on us—those rival visions of flourishing seep into us ever so slyly, very much under the radar of our intellects. If an education is going to be Christian, it has to be a re-training of our hearts, a counter-formation to these secular liturgies.

But this brings us to a second implication: at their best, Christian schools are precisely the sorts of educational institutions that get this. In other words, in the very DNA of Christian schooling is already an intuition about the importance of our second, sentimental education. Listen again to Brooks:

This second education doesn’t work the way the scholastic education works. In a normal schoolroom, information walks through the front door and announces itself by light of day. It’s direct. The teacher describes the material to be covered, and then everybody works through it.

The knowledge transmitted in an emotional education, on the other hand, comes indirectly, seeping through the cracks of the windowpanes, from under the floorboards and through the vents.… The learning is indirect and unconscious….

I find I can’t really describe what this landscape feels like, especially in newspaper prose. But I do believe [Springsteen’s] narrative tone, the mental map, has worked its way into my head, influencing the way I organize the buzzing confusion of reality, shaping the unconscious categories through which I perceive events. Just as being from New York or rural Georgia gives you a perspective from which to see the world, so spending time in Springsteen’s universe inculcates its own preconscious viewpoint (Brooks, “Other Education”).

Brooks can’t quite imagine a school that isn’t just “scholastic;” he can’t quite imagine a school that provides a “second” education. But that, it seems to me, is precisely the mission and vision of Christian schools. Christian education is a holistic vision for the formation of the whole person, equipping minds and forming hearts, educating our love by aiming our desire toward God and his kingdom. What should distinguish Christian education is just this holism, precisely because a biblical picture of the person helps us appreciate both theory and practice, both cognition and affect, both knowledge and desire. An integral Christian education doesn’t separate head and heart, intellect and emotion. Christian schools are unique precisely insofar as they very intentionally offer both a “first” and “second” education. And such schools are nested in other communities of practice, such as the church and home, which are partners in this “other” education.

So what does this have to do with stories? Well, our hearts traffic in stories. Not only are we lovers, we are also story-tellers (and story-listeners). As the novelist David Foster Wallace once put it, “We need narrative like we need space-time; it’s a built-in thing” (8). We are narrative animals whose very orientation to the world is most fundamentally shaped by stories. Indeed, it tends to be stories that capture our imagination—stories that seep into our heart and aim our love. We’re less convinced by arguments than moved by stories. (So Brooks, following the psychologist Jerome Bruner, distinguishes “paradigmatic thinking” that traffics in logic and analysis, from the “narrative mode” that weaves together our world on the level of the imagination [The Social Animal, 54–55]). The philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre says that stories are so fundamental to our identity that we don’t know what to do without one. As he puts it, I can’t answer the question, “What ought I to do?” unless I have already answered a prior question, “Of which story am I a part?” It is a story that provides the moral map of our universe.

Stories, then, are not just nice little entertainments to jazz up the material; stories are not just some supplementary way of making content “interesting.” No, we learn through stories because we know by stories. Indeed, we know things in stories that we couldn’t know any other way: there is an irreducibility of narrative knowledge that eludes translation and paraphrase.

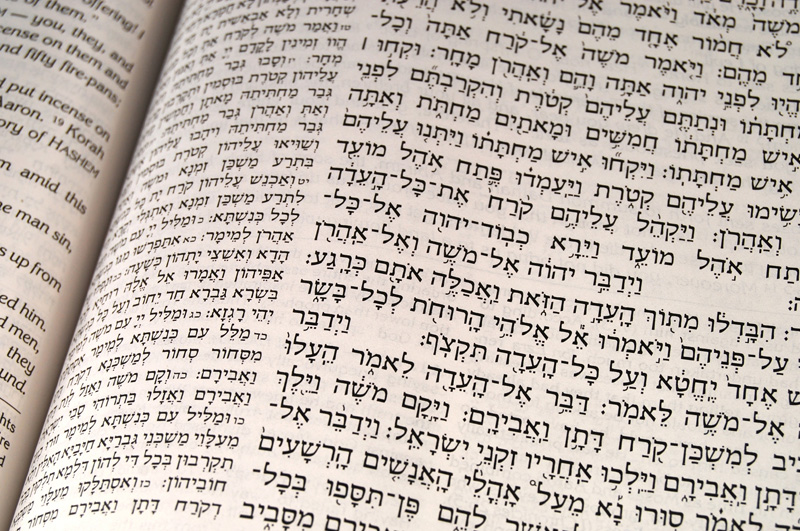

In his discussion of education amongst the people of Israel, Old Testament scholar Walter Brueggemann captures the point: In the Torah, when a child asks a question, the teacher’s response is: “Let me tell you a story.” For the people of God, he continues, story “is our primal and most characteristic mode of knowledge. It is the foundation from which come all other knowledge claims we have” (22–23).

So it is crucial that the task of Christian schooling is nested in a story—in the narrative arc of the biblical drama of God’s faithfulness to creation and to his people. It is crucial that the story of God in Christ redeeming the world be the very air we breathe, the scaffolding around us, whether we’re at our Bunsen burners or on the baseball field, whether we’re learning geometry or just learning to count. All of the work of the Christian school needs to be nested in this bigger story—and we constantly need to look for ways to tell that story, and to teach in stories, because story is the first language of love. If hearts are going to be aimed toward God’s kingdom, they’ll be won over by good storytellers.

Learning Stories

A holistic Christian education invites students into the incredible story of what God is doing in Christ, redeeming and restoring and renewing this broken but blessed world. As a “whole” education, Christian schooling embeds students in a community whose practices—ideally—function as compressed, embodied performances of this story. Such Christian schooling stages the drama of redemption and invites students—indeed, all of us—to see ourselves in the play. Christian schools are one of the “actor’s studios” that trains the people of God to play a part of this “act” of the drama of redemption. (Craig Bartholomew and Michael Goheen, creatively drawing on the work of N.T. Wright, describe the church’s mission as “act 5” of the drama of redemption in The Drama of Scripture.) To receive a Christian education is to learn this story, not just as a bit of information stored in our heads, but as an entire imagination that seeps into our bones.

But I would add one final role for story in Christian education. If we are going to invite future generations into this adventure that is Christian schooling, we need to share stories about it. If Christian education is going to have a future, it needs to be attractive—and the attractional pull will not come from airtight arguments or legalistic rules or data about “outcomes.” If Christian education is going to continue to capture the imagination of future generations, they will be captured by the stories we tell. Indeed, the alumni of our schools will be the living epistles that embody this story. Telling their stories will provide a winsome witness to the unique formation they received in Christian schools.

Let me close with one of my own stories, not because it’s earth-shattering or exemplary, but just to try to put some flesh on these bones. I could tell you all kinds of stories about academic excellence and rigorous learning. I could also share wonderful experiences of a curriculum rooted in a big vision of God’s care for his creation, equipping students to be ambassadors of his kingdom in every sphere of culture. I’d be happy to testify to the concern for justice that my children have absorbed through their Christian education. Let’s take that for granted. Instead, I want to give you a peek at what’s unique but almost intangible about Christian education.

The story comes from an episode almost ten years ago. When we moved to Grand Rapids from Los Angeles, one of our children had a particularly difficult transition. We had sort of underestimated the angst our relocation had generated for him, and we didn’t quite understand that all his acting out was his way of trying to grapple with this disorientation. The notes and calls coming home were a steady stream of concern. We worried that he’d wear out his welcome at Oakdale Christian School before he ever really got started!

It came time to attend our first parent-teacher conference with Mrs. Braman. We were braced for the experience, expecting to be both scolded and embarrassed. We were ready to face the music about our failure as parents. So we sat down with Mrs. Braman and she quickly announced, “I love your son.” We tried to point out to her that we were the Smiths—was she perhaps expecting a different family? Had we shown up at the wrong appointment? But what we quickly learned was this: she loved our son. She loved our son because she was a teacher caught up in the messy narrative of redemption, the story of God’s gracious love in Christ, the drama of God’s hope for this broken world. She loved our son because she knew that our gracious God plays a long game, and isn’t surprised by anything. And she saw in our son the disciple in the making, the follower of Jesus buried in all his fear and bewilderment. And she loved him.

And for my son, that wasn’t just care; it was an education. He saw love modeled. He absorbed aspects of God’s story intangibly, through his teacher’s example of the virtues. He received a “second” education in that experience, which has trained his own love and compassion. This was one part of an embodied curriculum that taught him, over the years, what really matters—that God’s kingdom is concerned with the marginalized, the outsiders, the vulnerable, even though Mrs. Braman didn’t say a word about that. That sort of education happens every day, and over a lifetime, in schools like Northern Michigan Christian School. And we can’t afford to lose it.

So as we celebrate one hundred years of God’s faithfulness to Northern Michigan Christian School, let’s not just saunter down memory lane. Let’s remember in order to hope—to hope and expect even bigger things from the Spirit who loves to surprise us. Let’s be that community that sees Christian schools as an arm of the very mission of God. With outsized hope, let’s imagine how all God’s children could be shaped and formed by such an education. Let’s renew the sacrificial love of generations past who made it possible for us to be celebrating here today. As a community of faith, caught up in the story of God in Christ, let’s recommit ourselves to our baptismal promises, with a renewed passion for Christian schooling not as a “private” education but as a “sentimental” education, an education of the heart based on a pedagogy of desire. Let’s embrace Christian education as the counter-formation that is crucial for the future of the church’s mission in the world. And let’s not just tell the next generation; let’s show them.

Works Cited

- Bartholomew, Craig and Michael Goheen. The Drama of Scripture: Finding Our Place in the Biblical Story. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2004.

- Brooks, David. The Social Animal: The Hidden Sources of Love, Character, and Achievement. New York: Random House, 2011.

- Brooks, David. “The Other Education.” New York Times. Web. November 26, 2009. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/27/opinion/27brooks.html?_r=1

- Brueggemann, Walter. The Creative Word: Canon as a Model for Biblical Education. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1982.

- Medina, Jennifer. “Proms as Do-Overs for Adults.” New York Times. Web. May 12, 2011. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/12/us/12prom.html?_r=1&scp=1&sq=adult%20prom&st=cse

- Wallace, David Foster. “Fictional Futures and the Conspicuously Young.” The Review of Contemporary Fiction. Web. (1988). http://www.theknowe.net/dfwfiles/pdfs/ffacy.pdf