“Art critics talk about art. Artists talk about where to buy good turpentine.”

—George Santayana

Reading Practically Human made me want to attend Calvin College. Fortunately for me, I already have; unfortunately for me, Practically Human had not yet been penned when I was there. I spent the entirety of my undergraduate career matriculating at Christian liberal arts colleges—six years in total immersed in the humanities, first as an English and communications double major, and two more in secondary education, English. Had Practically Human been in my arsenal at that time, I would have been better able to answer those who interrogated me as to the practicality and profitability of a knowledge base centered around such things as the beauty of iambic pentameter and the importance of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass in redefining the collective American identity. When my personal “cloud of witnesses” asked me, “So how do you intend to pay off your loans with that major?” editors and Calvin College professors Gary Schmidt and Matthew Walhout would have provided a much more articulate defense than whatever loosely crafted argument I presented at the time. Nearly a decade has passed since I walked the halls of Calvin as a student, but in that time I have watched as the seeming ivory tower abstractions of my humanities professors took on flesh to become my red-blooded reality. Practically Human serves as a blueprint for this scholarly transfiguration, its essays outlining, from myriad angles, why a humanities-based education matters, and, perhaps more significantly, how such an education can work itself out in the lives of its graduates.

Written with a prospective-student demographic in mind, Schmidt, Walhout, and a collection of other Calvin College professors from across a variety of fields examine the power, profitability, and practicality of engaging the world from a Christian college humanities perspective. While such assertions may prove cold comfort for the recent grad who must rub two pennies together for heat because she cannot afford to turn up the furnace with her first-job paycheck, the truths evaluated in Practically Human are a slow and lasting burn that remind readers that to be schooled under an educational philosophy grounded in a deep appreciation for human nature and human “flourishing” (as Schmidt and Walhout call it) in all its complexity, is to be spiritually and intellectually empowered. Empowered individuals become agents in their own lives, and whether one chooses to work in investment banking, teaching, shipbuilding, or the ministry, when a person is empowered, she will naturally effect change.

Perhaps this is the undergirding message of Practically Human: when a student is given the opportunity to examine the human condition, with all of its warts and scars and from every angle possible—through music and rhetoric as much as though literature and art—he or she cannot help but learn the wisdom of compassion. I don’t know about you, but as a teacher, when the objective is to create empowered, compassionate, “flourishing” human students, I want to see the lesson plan. The essays in this collection are just that: a comprehensive set of concrete examples of the ways in which different humanities courses work to shape students into graduates whose understanding of the world is theoretically and functionally compassionate. Understood as an apologetic for Christian humanities education, the essays effectively prove the importance of a humanities perspective across a variety of fields.

The collection begins with an introduction from Schmidt and Walhout, who attempt, among other things, to outline the viability of a Christian humanities education in such a way that both confronts and decommissions the ever-present worldview that assumes a vocational dichotomy between money and meaning. Schmidt and Walhout write:

Colleges like Calvin face a constant barrage of questions and criticisms in the mass media, all suggesting that higher education wastes resources. The criticism focuses on the supposedly “impractical” fields known as the humanities . . . [but] great ideas are like the soil in which human beings grow. A humanities education is like the fertilizer that strengthens a student’s intellectual roots, increases resistance to disease, and enhances the production of good fruit . . . Students do not have to choose between developing job skills and developing character. This is not an either-or proposition. A college is not a factory farm that cranks out intellectually fattened graduates to be consumed in the labor market. Neither is it a glorified extension of summer camp, where young adults can escape rigorous discipline or prolong their childhood. Instead, a college education should weave together two very serious, very real goals. It should prepare you for a career, and it should also give you wisdom for the life you will live both within and beyond the workplace (12–14).

The first essay in the collection, by philosophy professor Lee Hardy (“Greater than Gold: The Humanities and Human Things”) outlines the importance of philosophy in creating humane learners. Hardy reminds his readers of the life of Socrates, who taught that for one to attain wisdom, one must first humble oneself and admit ignorance before the truth will present itself. Hardy argues that the true goal of a humanities education is that which is priceless—not a solid 401K plan, but rather, wisdom. In a related vein, interdisciplinary studies of science professor and Practically Human editor Matthew Walhout examines the value of discernment as a practical skill. In a field most often understood as entirely empirical in approach, Walhout describes for his readers the power of context and history (specifically in regards to science and religion) in realigning one’s worldview. Walhout writes: “Prior to our readings and discussions, [my students] had not understood how science is fundamentally connected to philosophy, religion, and to cultural attitudes . . . humanities-style reflection led [them] through key existential moments and helped them find their bearings in the world” (82–83).

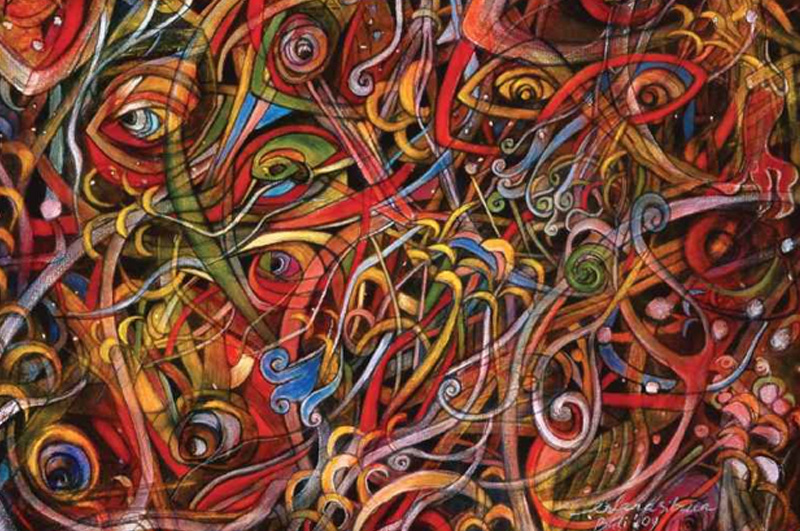

Beyond wisdom and discernment, several essayists explore the questioning of alterity, or “othering,” as a pathway to empathy. In “Good Looking,” professor of art history Henry Luttikhuizen draws attention to the power of cultural and historical context in shaping our ways of “seeing” ourselves and others (66). Luttikhuizen argues that when we are asked to understand the contexts of those other than ourselves, empathy is naturally fostered as a result (68). Likewise, David I. Smith argues in his, “Shouting at your Neighbor: Why We Bother with Other Peoples’ Languages,” that language classes provide students with the opportunity to “learn to listen to those who are not like us, to love our neighbor who grew up in a different place, to show willingness to take a step in their direction to see what we might receive and what we might have to give” (134). Professor of history William Katerberg tells us that, “understanding the past requires us to see both what is close to how we experience the world and what looks foreign and distant . . .” (44). Why seek to understand what is foreign? Why seek to understand ourselves from the perspective of the “other”? Because, as Katerberg explains, doing so is in fact part of one’s journey toward self-knowledge, the journey that is the “long route to the self” (Kearney qtd. in Katerberg 49).

In an epistolary style reminiscent of writer Rainer Maria Rilke in his Letters to a Young Poet, literature professor Jennifer Holberg’s “Why Stories Matter More Than Ever: A Letter to a Friend Just Beginning College” acts as a treatise on the importance of storytelling and narrative in creating faithful and attentive human beings. As Holberg notes, “The going currency these days is not fact, but narrative . . . we are story-shaped people” (101). Holberg quotes former Calvin professor Henry Zylstra, who argued that literature gives us “more to be Christian with” (103). Further, Holberg writes that reading literature that is grounded in the “splendor and squalor” of our human condition” (105), and “help[s] us fulfill our highest calling of loving God and loving our neighbors” (103). As we learn to “read deeply, to write compellingly, to research thoroughly, and to think critically” (99) we learn to be attentive; in attentiveness, we learn empathy.

As an educator and writer, I admit that I am most drawn to the essays grounded in the study of literature and writing. Not the least of these was the essay written by writing professor and coeditor of this book, Gary Schmidt. In his essay, “Why Come to College to Study Writing?” Schmidt embodies the collection’s subtitle when he writes from the “heart” of his vocation. His thesis is clear and direct: “This is why you come to college to study writing: because your words can change a reader forever” (110). Schmidt goes on to elucidate the responsibility of the writer to act as servant to her readers and the world. He concludes by telling a story about teaching writing to a room full of middle school students, and in particular, a red-shirted boy who is hands-covering-face reticent to tell his story to the class at large, but eager to regale Schmidt one-on-one in what reads as an emotionally charged and vocationally affirming moment. Schmidt concludes: “You write so that the kid in the red shirt at the back of the room will see in your writing more than what he is, or has, or has experienced. You write to invite him to a larger world so that his hands will begin to come down from his face” (122). For me, this essay was a “the veil is rent in two” moment. Schmidt’s words read as a testimony to the sacred task that is educating.

As a senior student at Hope College, another Christian liberal arts institution, I spent a semester learning in an off-campus program called the Oregon Extension. The program focused primarily on the humanities, and each student took on several independent projects based on their own interests. While reading Kenneth Leong’s The Zen Teachings of Jesus, I encountered a quote from writer and philosopher George Santayana that remains with me today. He writes, “Art critics talk about art. Artists talk about where to buy good turpentine.” At their core, the essays in Practically Human evince the truth to which Santayana was alluding. An education in the humanities is about exploring the intangibles of empathy, beauty, suffering, compassion, and wisdom, yes; but perhaps more importantly, an education in the humanities from a Christian college not only teaches these principles, but it empowers its students to act on what they have learned. Rather than simply philosophize about empathy, students are encouraged to slap a pair of work gloves on their empathy and go into the world and act with compassion, in whatever form their God-given talents take.

If I have any major critique of Practically Human, it is simply this (and I realize this may be unfair as it is out of scope with the editors’ focus): because all of the essays are written by Calvin professors, I can’t help but wonder how the conversation would be more nuanced and colorful with the inclusion of humanities perspectives from professors of other Christian colleges and universities. With more and varied voices, the collection would feel less a tribute to Calvin College in particular, and more an argument for the importance of Christian humanities education in general. That said, as an apology for the practicality of a Christian college humanities education, Practically Human is as affective as it is effective—a testament to the “hearts and minds renewing God’s world” mission of its sponsoring institution. For educators at all levels, but perhaps especially for secondary and postsecondary teachers, Practically Human is a read worthy of your precious free time. If your personal economy isn’t measured in time, I endorse this collection of essays for no other reason than that it gives its readers, as Zylstra and Holberg suggest, “more to be Christian with.”