Kevin Mirchandani and Nina Pak Lui

As educational researchers and practitioners, we have identified the following challenges for teachers in the K–12 Christian school context: capacity building, professional learning opportunities, and sustainable infrastructure to support goals of lifelong learning. The needs in our local teacher education program include finding appropriate field placements, engaging in collaborative community partnerships, and connecting course learning to the complex realities of educational practices. We believe that bridging theory and practice and creating a culture of transformative professional learning cannot be accomplished in isolation. Jeanne Maree Allen states that “in-field and on-campus components of teacher education will remain disjointed while they are taught and overseen by people who have little ongoing communication with each other” (742). Research indicates that “educational stakeholders, including universities, school districts, schools, and governments, need to work collaboratively to spur change” (Schnellert et al. 2). For this reason, when educators in K–12 school communities and local teacher education programs work collaboratively, their partnership can strengthen professional learning and their respective school’s vision and mission.

[W]hen educators in K–12 school communities and local teacher education programs work collaboratively, their partnership can strengthen professional learning and their respective school’s vision and mission.

In this article, we offer a narrative of how faith-based K–12 schools can work with their local university, drawing on shared principles from Indigenous ways of being, Christian relationality, communities of practice, and community-based research. We will first situate ourselves, then describe the co-created relationship between the university and the K–12 school, and finally share the outcomes from this collaborative partnership.

Situating Ourselves

Trinity Western University (TWU) is a small, private, faith-based liberal arts institution, located on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territories of the Kwantlen, Katzie, and Stó:lô First Nations in British Columbia (BC). Post-degree pre-service teachers have the opportunity to participate in a two-year teacher education program in the School of Education at TWU that culminates with professional certification. Langley Christian School (LCS) is a K–12 independent Christian school located on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the Kwantlen, Katzie, Matsqui, and Semiahmoo First Nations people.

Teacher educators in this network explore new ways to strengthen the teaching profession as a whole through listening, critically questioning, and challenging processes of teacher education.

I (Nina) am currently an assistant professor of education in the School of Education at TWU who is actively engaged in a province-wide professional learning network. Teacher educators in this network explore new ways to strengthen the teaching profession as a whole through listening, critically questioning, and challenging processes of teacher education. I am particularly interested in the journey toward decolonizing the self and reflexively transforming practices in teacher education and beyond. My relationship with the university’s Siya:m (a word from the Stó:lō people describing a leader recognized for wisdom, integrity, and knowledge) deepens my understanding of how local Indigenous principles and my Christian faith can respectfully guide the co-construction of new pedagogies with pre- and in-service teachers and communities.

I (Kevin) work as the K–12 director of the Instruction and Christian Foundations department at Langley Christian School and adjunct professor in the School of Education at TWU. I am particularly interested in the intersection of Christian faith-informed leadership and how we think about sustainable educational improvement. I am also an educational change thinker, which means I spend a lot of time thinking about past and present realities that people and their faith communities experience and how to approach problems formatively with theological, communal, and strategic ideas. I believe there are distinctly Christian ways of being that are crucial for leadership aimed at educational change and professional learning.

It was the late fall of 2020, when we were planning our respective teacher education courses (Nina: EDUC 401 Assessment for Learning; Kevin: EDUC 465 Middle/Secondary Instruction) in the School of Education, that we identified a need for understanding the realities of the classroom and making meaningful connections to course learning (OECD 93). Nina was also inspired by fellow teacher educators across universities in BC who approach teacher education through developing multi-partner communities of pedagogical inquiry (Schnellert et al. 2). Given that our respective institutions are situated within ten minutes of each other geographically, we entered into conversation about relationality, location, and how to co–create spaces in which pre- and in-service teachers, university faculty, and school leaders could learn from and with each other. Our deep hope was to see transformation of educational thinking and practice and provide an opportunity for members of our communities to thrive in professional learning together (Schnellert et al. 2).

[W]e entered into conversation about relationality, location, and how to co–create spaces in which pre- and in-service teachers, university faculty, and school leaders could learn from and with each other.

Guiding Questions

The questions that guided us in all of our thinking and planning were the following:

- How can course learning in the university context be closely aligned to local school practices during initial classroom experiences?

- What would be the impact on both of our communities if we worked collaboratively toward professional learning?

Underpinning Principles of the Community Partnership

We found the following four principles to be particularly helpful when planning our community partnership.

- Indigenous Ways of Being

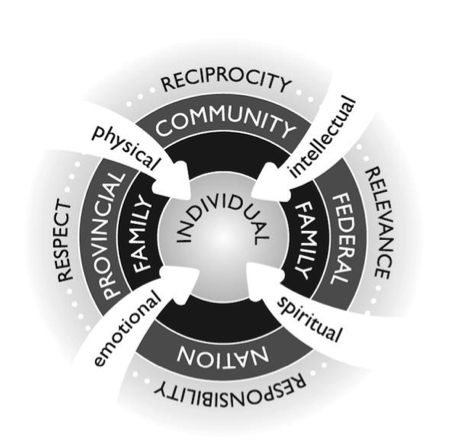

We believe that “Indigenous principles offer new ways to think about teacher education” (Sanford et al. 31). Therefore, our understanding of relationality is informed by “Indigenous wisdom, grounded in a tradition where understanding is about relationships with other people and ideas in interconnected ways” (Schnellert et al. 4). Our community partnership program borrows ideas from the “four Rs” of holistic Indigenous education: responsible relationships, reciprocity, respect, and relevance (Cull et al. 26; see fig. 1). Professional learning for pre- and in-service teachers at LCS and TWU is mutually respectful and beneficial. Relational accountability occurs by continuously reflecting on the potential impact of our intentions on the community (26). Our partnership also aims to honor the knowledge and gifts that each person brings and strives to create meaningful and sustainable community engagement (26).

- Christian Relationality

Christian community and relationality grounds itself in the mystery and learning community of the Trinity (John 10:30; 14:16–17). Pedagogically, the community of the Trinity is understood in Jesus’s example of incarnational teaching in the apprenticeship of his disciples (Mark 3:13–15; Matt. 4:19), in his instruction about God’s community of creation (Matt. 5:1–12), and in the reflective and experiential dialogue that takes place between Jesus and his disciples (Luke 9). We also ground our beliefs about community partnerships in the biblical notion of shalom (1 Pet. 4:8–10), which is a description of how both individuals and communities acknowledge the truth and engage in reconciliation, healing, and restoration as they thrive in a deeper peace that comes from God (Woodley 10).

- Communities of Practice

Social learning anthropologist Jean Lave and social learning theorist Etienne Wenger in their work on situative learning describe communities of practice as an intrinsic set of conditions that provide support to make sense of a community’s social structure, practices, relational dynamics, and motivations for learning (98). In the language of Lave and Wenger, when newcomers to a field furnish their social worlds in their communities, they transform into practitioners associated with the identity and motivations of the community (122). Some of the challenges we have found in teacher education are how power is inequitably distributed among community members and how knowledge is transmitted rather than co-created. We believe that deep and transformative learning takes place when learners in the community are cared for and honored as whole persons.

- Community-Based Research

Community-based research (CBR) is a collaborative and decolonizing approach that equitably involves all partners in the research process. CBR recognizes the unique strengths that each person involved brings (Caine and Mill 15). Partners identify an issue of importance to the community and combine knowledge and action in achieving change. Core elements of CBR include the following: mutual trust and respect, capacity building, empowerment, accountability, and ownership (16). Local knowledge and co-creation of knowledge is useful to the community (27). Mutual respect and trust are at the center of the partnership between TWU and LCS, as well as building pedagogical capacity among pre- and in-service teachers. The level of participation of both community and academic partners is dynamic and continuously negotiated because power is a shared responsibility (31).

Note: If you would like to see an artifact of learning from the community partnership, please visit this link. We share this artifact of learning from one of the post-degree pre-service teachers with their consent.

Kevin Mirchandani, PhD Student in Educational Studies at Biola University, is the K–12 director of Instruction and Christian Foundations at Langley Christian School and adjunct professor of Education and Leadership Studies at Trinity Western University. The focus of his studies is the intersection of Christian faith-informed leadership and sustainable educational change.

Nina Pak Lui, PhD Student in Community Engagement, Social Change, and Equity at the University of British Columbia, is an assistant professor and the post-degree program coordinator in the School of Education at Trinity Western University. The focus of her studies is a journey toward decolonizing the self and reflexively transforming practices in teacher education and beyond through community-based research.

Works Cited

Allen, Jeanne Maree. “Stakeholders’ Perspectives of the Nature and Role of Assessment during Practicum.” Teaching and Teacher Education, vol. 27, no. 4, Jan. 2011, pp. 742–50, https://doi-org.ezproxy.biola.edu/10.1016/j.tate.2010.12.004.

Caine, Vera, and Mill, Judy. Essentials of Community-Based Research. Routledge, 2016,

Cull, Ian, et al. Pulling Together: A Guide for Front-Line Staff, Student Services, and Advisors.

BC Campus, 2018, https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationfrontlineworkers.

Lave, Jean, and Etienne Wenger. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation.

Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). “Innovative Learning Environments.” Center for Educational Research and Innovation. OECD Publishing, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264203488-en.

Sanford, Kathy, et al. “Indigenous Principles Decolonizing Teacher Education: What We Have Learned.” In Education, vol. 18, no. 4, 2012, pp. 19–34, https://doi.org/10.37119/ojs2012.v18i2.61.

Schnellert, Leyton. “Exploring the Potential of Professional Learning Networks.” Professional Learning Networks: Facilitating Transformation in Diverse Contexts with Equity-Seeking Communities. Edited by Leyton Schnellert, Emerald, 2020, pp. 1–15,

Schnellert, Leyton, et al. “Developing Communities of Pedagogical Inquiry in British Columbia.” Networks for Learning: Effective Collaboration for Teacher, School and System Improvement. Edited by Chris Brown and Cindy Poortman, Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2017, pp. 56–74.

Sharma, Umesh, and Jahirul Mullick. “Bridging the Gaps between Theory and Practice of

Inclusive Teacher Education.” Oxford University Press, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1226.

Woodley, Randy. “Shalom and the Community of Creation: An Indigenous Vision.” Eerdmans, 2012.