We all know the story. Jesus standing next to the woman caught in adultery, looking at the circle of leaders granting them permission to cast the first stone. And they gradually all leave, “the older ones first” (John 8:9).

Denise teaches a difficult class of grade 2 students. Owen is by far the most notorious, able to create fear and frustration in his classmates as well as people five to six times his age. Denise knows how she used to cover up her lack of confidence when Owen would “strike” by “striking back” at him with all the power she possessed as an adult. After three months of intentionally nurturing a relationship with him, honoring him for who is rather than who she wants him to be, Owen is responding. He trusts her and seeks her out when he is troubled by his own inability to control his behavior. A colleague recently asked her, “What are you doing with Owen? He seems so settled lately.” Denise responds: “I am choosing to have a relationship with him.”

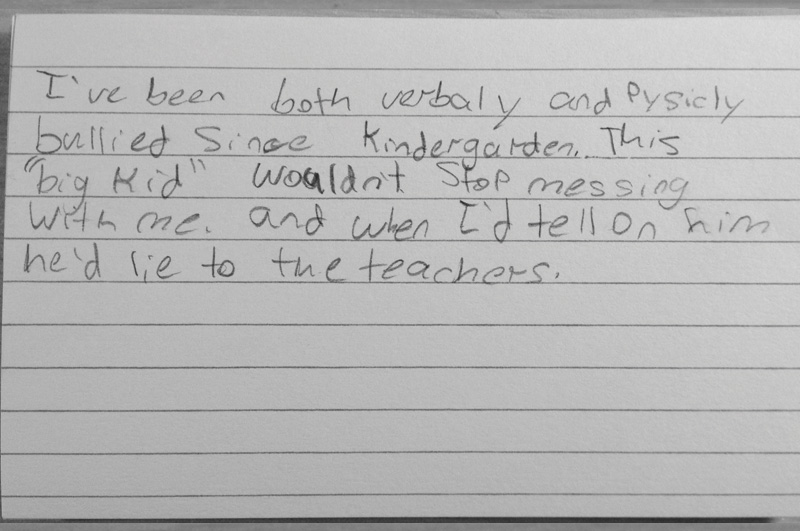

Bullying amongst youth continues to dominate dialogue in almost all sectors of society. This is both hopeful and discouraging—hopeful in that people feel deep concern about harm that is caused through relationships; discouraging that even after years of intense effort and research, the problem with bullying does not seem to be diminishing. In fact, research indicates that all our efforts in the context of education have limited impact and in some situations may actually be perpetuating the problem (Ttofi and Farrington; Seeley et al.). What is going on? Where do we turn to truly make a difference?

A Different Vantage Point

In this article, I encourage us all to consider that Jesus (in the incident with the religious leaders accusing the adulterous woman) gives us the answer, albeit an answer that is not easy to accept. We need to shift our attention from the youth engaged in and affected by bullying behavior, to us—the adults in their lives. Phil Gatensby, in a poignant piece on YouTube, says it well.

The problem with youth today? It’s us. It’s the adults. We say to youth: “We want you to be honest,” but are we honest? We say to the youth, “I want you to show respect!” Do we show respect to one another or to youth? <youtube.com/watch?v=9xFG2t5JIFU>

As educators and upstanding citizens in North America, we might be tempted to become defensive and list all the wonderful things we are doing with and for our students—and there are many. But in spite of all our good intentions, we contribute to a larger society that is constantly bombarding our youth with aggressive messages that are difficult to decipher and resist. Consider briefly Toronto mayor Rob Ford, accepted behavior in professional sports, the words used by political leaders to describe opponents, Black Friday, and the reality series Survivor. Consider the rise in child pornography, growing underage sex trade, sexualized fashion designs for children, labor strikes, and military spending. Consider the regimented school day, standardized testing, honor rolls, punitive consequence-dependent codes of conduct, rewards-based classroom management strategies. If we are honest, we will admit that bullying tactics are woven throughout each of these examples and are just the tip of an iceberg that is grounded in an economy-driven worldview that reduces people to objects to be manipulated. Bullying is complex. But rather than a bounded specific problem, it is in reality a symptom of much deeper issues of relationship in which we are all engaged.

Familiar Territory

For many years, bullying has been conceptualized and defined as an act that includes three key components:

- harmful, aggressive behaviors

- that are repeated over time

- between people of unequal power status (Olweus)

More recently, definitions highlight that bullying is “a relationship problem where an individual or group uses power aggressively to cause distress to another” (Pepler). This is a subtle but important shift, as it points to rethinking philosophical foundations. Whereas the earlier definition draws on am individualistic worldview that emphasizes the behavior of particular people, the latter opens the door to a relational, ecological worldview that emphasizes the interconnectedness of people with each other and with their environment. In the first definition, most solutions to bullying are variations of external social control; in the latter, bullying is understood as part of a broader social context with the solutions arising from social engagement (Morrison). Given that our society is steeped in individualism, characterized by competitive attitudes of “survival of the fittest,” acting out of a relational worldview is countercultural and challenging, even as followers of Christ. In spite of the inherent, God-given pull we feel to live relationally, in our current North American context, this landscape is actually foreign. As adults, we assume it is familiar territory, but in reality we have difficulty finding our way in it. To illustrate, consider UNICEF reports on the well-being of children in rich countries. In 2013, Canada ranked twenty-fifth and the US ranked twenty-seventh out of twenty-eight countries on quality of relationships of youth with their family and peers. The 2007 report placed Canada eighteenth and the US twenty-fifth out of twenty-five countries on eating main meals together several times a week; Canada ranked twenty-third and the US eighth out of twenty-five on talking with parents several times a week.

To further illustrate, consider how the individualistic and relational worldviews are straddled when governments and schools create policy to address bullying. As I write this article, our province (Newfoundland and Labrador) is implementing anti-bullying legislation and a revised safe and caring schools policy that has as its goal the reality that no child or adult will be afraid to be in school. The work is commendable as it acknowledges clearly the importance of healthy relationships and the need for all people associated with the school to be responsible for nurturing well-being. However, the polished philosophical statements are then girded on all sides with policies, codes, and checklists that focus on addressing negative behaviors arising between students or between students and teachers, and nurturing more appropriate behaviors through programs that reward good behavior and observable virtues. This attempt to nurture healthy, authentic relationships with external rewards and consequences for individuals undermines the potential for developing relational, safe, and caring school climates where people look after each others’ well-being authentically. It is like trying to mix oil and water. In the field of education, we have known this for many years (Kohn). We also realize that punishment is a quick fix to meet adult need for control (Coloroso; Ungar) and that surveillance and incentives reduce overt bullying in busy areas, but do little to address the predominant covert nature of bullying (Pugh and Chitiyo). Yet we ignore insights such as these repeatedly and develop one more policy document that can only be implemented if we put adults in place to police it. It is ironic that policy, police, and policing all share the same root word.